- Home

- Jeff Duncan

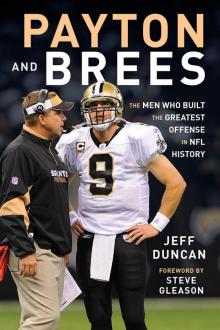

Payton and Brees

Payton and Brees Read online

This book is dedicated to Saints fans and the people of the great city of New Orleans, who deserve leaders like Drew Brees and Sean Payton.

Contents

Foreword by Steve Gleason

Prologue

1. Finding the Pilot

2. Aligning in New Orleans

3. Destined to Be a Saint

4. The Parcells Effect

5. Child of Destiny

6. Alike Yet Different

7. The Sean Payton Offense

8. The Winchester Mystery House

9. Blitzing the Defense

10. The Grind: Putting Together the Plan

11. Finding the Golden Nugget

12. Calling the Shots

13. The Supercomputer

14. Maxing Out

15. Fighting the Stereotype

16. Trust and Confidence

17. “Who Throws That Ball?”

18. Two Minutes to Paradise

19. Driven to Compete

20. The Fire and Fury of Sunday Sean

21. Don’t Eat the Cheese

22. The Near Divorce

23. The Saint Patrick’s Day That Almost Was

24. In NOLA to Stay

25. 40 Is the New 30

26. A Tree Grows in Baton Rouge

27. The Payton-Brees Legacy

Acknowledgments

Photo Gallery

Foreword by Steve Gleason

I met Sean Payton and Drew Brees 14 years ago, in 2006. At the time, the Saints and the city of New Orleans were just in the initial stages following the agonizing destruction of Hurricane Katrina. I played on the team for the previous six seasons and had fallen in love with the unique culture of this community—not to mention a daughter of the community I found uniquely loveable. While I was confident the people of New Orleans would recover resiliently, I was not so sure about the Saints organization. I had more pressing personal concerns. The family of my future wife, Michel Varisco, had their home completely destroyed. Even more personally, when Coach Payton first set eyes on me in the Saints cafeteria, he assumed I was just a long-haired team equipment manager.

Along with Michel’s family and the city of New Orleans, I was working to find a return to success after a really difficult year following Hurricane Katrina. Ultimately, Drew Brees and Sean Payton would be the catalysts of that return—our collective rebirth.

From a personal perspective 14 years later, I consider Coach Payton and Drew Brees my brothers. Yeah, I convinced Payton that I was more than an equipment manager during 2006 training camp. But three years after I retired from the NFL, I was diagnosed with ALS, a hurricane of a disease. Painful and agonizing. Brees and Payton have been immensely supportive of me both publicly and privately. I am so grateful for their friendship. I love them.

At some point during the Saints team and organization’s transition, the phrase “We will walk together forever” emerged. I have remained in New Orleans and I am raising a family with Michel. Coaches and players have come and gone, as we all do, but for the past 14 years, I have gotten to see Drew and Coach at the facility, or the Dome, or Mardi Gras, or a fundraiser, or even at the house. Both of these guys ushered in a change of plans, a change of mind-set, and a change of heart, not only with the Saints organization, but the entire New Orleans region. In a completely unprecedented way, since the 2006 season, the people of this city, region, and state can all proudly say, “We will walk together forever.”

I played all eight years of my NFL career with the New Orleans Saints. I made the team after a free-agent tryout midway through the 2000 season. It was your standard workout: 40-yard dash, bench press, standing long jump, agility drills. Afterward, the scouts took me and the other tryout players for a meal before our flights back home. I was surprised at their choice of dining establishment: a grungy restaurant with bars on the windows in a neglected neighborhood that served cold fried chicken from a buffet. To say the least, it was not the kind of experience a first-class organization would project. It was a little thing. But it said a lot. I got a call a week later to join the team, and two weeks after that I was on the field with the Saints playing against John Elway and the Denver Broncos.

Payton and Brees joined the team six years later in the wake of Hurricane Katrina. Before they arrived in town, the Saints teams I played on were talented but inconsistent. On any given Sunday, we could beat the best team in the league or lose to the worst. My rookie year, maybe 10 weeks after eating a buffet lunch behind barred windows, we won our first playoff game in franchise history. But we lacked the discipline and consistency necessary to be great.

When Coach Payton took over the team in 2006, he knew he needed to change things in the organization. He knew the perception and results would not change until the culture did.

First, he had to determine what kind of culture the organization had enabled and fostered for the previous 38 years. This required him to create a sense of urgency, not only among the players, but also the existing Saints staff, management, and ownership. In an organization that seemed pretty content with mediocrity, this was a monumentally enormous task from my perspective.

I think Coach Payton knew that this would require bold action early in his tenure. For existing staff and front-office personnel, Payton ensured he and his coaches were treated in first-class fashion. He pushed for his staff members to have more favorable car lease agreements and disallowed business operations staffers to enter and interrupt coaches’ meetings. Coach Payton wanted his coaches to be treated like company executives.

For the players, Coach Payton wanted to push the level of urgency. To set the tone, he hung signs around the training facility. The first sign I saw read: Saints Players Will Be Smart, Tough, Disciplined, and Well-Conditioned. It made me laugh. In an industry where players are coveted for their size, speed, and strength, I had doubts that this message was sincere. Messages like this became the theme. The coaches and management were continuously thinking about what these signs should say, underscoring their importance. They regularly changed and replaced them, sending the message that these principles were not simply collecting dust on the wall. It struck me as smart, a good first impression.

Early in the spring he made another strong impression. He told the team there was a three-year timeframe for drafted players. In Year One, players were given the benefit of the doubt as they were rookies or new to the team system. In Year Two, a transition to production would need to be observed. In Year Three, players would be at a crossroads with the team and should probably “update their résumé” if they weren’t being productive. He was creating a sense of urgency with every player on the roster.

Additionally, he promised that high-level decisions that turned out to be incorrect would not be supported simply to satisfy egos or balance the books. Marques Colston exemplified this philosophy. Colston was a seventh-round draft pick out of Hofstra who clearly outperformed former first-round pick Donté Stallworth during training camp. The Saints traded Stallworth midway through training camp and elevated Colston to the starting lineup. Message sent. No player’s roster spot was guaranteed—regardless of the amount of money invested in the individual player. As a former undrafted free agent who was trying to make an impression on the new coach, I already felt plenty of urgency. But I was reassured by Payton’s actions. He meant what he said about the best players making the team. I felt I had a chance to be one of those players. Coach Payton’s ability to persuade management to make the correct “team” decisions was refreshing.

Coach Payton also instituted a disciplinary system that consistently fined players for small transgressions like missi

ng meetings or being overweight. These fines were reported every morning at the team meeting and no further oration was implemented. Players were not given exemption, and the fines were generally preceded by a simple statement like, “These rules had been developed and agreed upon by the team.” This may not seem like a large factor in successful change, but as a player I saw it as vital. Not surprisingly, the discipline statistics in our games (penalties, mental errors, etc.) were greatly reduced as this change took place. The night before our first preseason game in 2006, Coach Payton made another strong impression. We were bused to a hotel in Jackson, Mississippi. When I was given my key, I went to my room and noticed the place smelled of mothballs and there was a hole in the sheetrock. This was early in the change effort, and I had my doubts there would be any real change with the new coach. This hotel solidified my doubts. We assembled a couple hours later for a team meeting and I anticipated Coach Payton’s reaction, if any, to the hotel quality. Impressively, he stood in front of the team and not only apologized for the hotel but promised with confidence and sincerity that we would never stay in a hotel like this while he was the head coach.

For the first time in my NFL career, a coach showed us he cared enough for the players to confront the organization and create change. I thought to myself, Maybe things are changing for the better after all. Coach Payton’s vision was starting to come into focus.

It helped that the team’s quarterback was helping Coach Payton communicate the plan. It’s impossible to understate how important the signing of Brees was to the franchise. While Drew’s talent was impressive, I think Coach Payton wanted him just as much for his leadership skills. At the player level, Drew helped communicate Coach Payton’s message and emphasized what was important in the organization. Drew’s passion for football was contagious to the rest of the organization. He took great risks by vocally demanding excellence from teammates but also by encouraging the team to develop an investment in each other.

Before Drew arrived, Aaron Brooks was the quarterback. Aaron was a nice guy and a supremely talented player. Unfortunately, he lacked the leadership skills necessary to quarterback a first-class team. When Drew arrived in New Orleans, he was a successful quarterback but not a perennial All-Pro, and he was coming off a potentially career-ending injury. He had his doubters in the media and even among the players.

Toward the end of training camp, Coach Payton asked Drew to address the team. At the time, I’m not sure that was something Drew was completely comfortable with. But he knew he had to find a way to be comfortable being uncomfortable if he was going to actually lead the team and help us achieve our lofty goals.

It was a risk for Coach Payton to identify Drew as the leader of a team he had joined just six months earlier. And it was a risk for Drew to expose himself as vulnerable to the potential scorn of other players. I remember being nervous for him. Remember, this was not the guy who holds several all-time NFL records, nor did he wear a Super Bowl ring—yet. It was in this moment, when Drew chose to address the team, I realized that anything was possible for Drew Brees. I saw greatness, through courage and genuine transparency.

It seems Drew was bolstered by the confidence Coach Payton instilled in him as he stood in front of the team and presented us with goals for the upcoming season. He also talked about the characteristics he thought were necessary to accomplish these goals. He communicated them clearly and confidently. It was a great speech. After that day, every Saints player knew No. 9 was our leader.

Drew continued to set the tone for the rest of the team with his work ethic. His car was regularly the first one in the parking lot in the mornings before practice and the last one to leave that night after practice. He had an almost unreasonable belief that the team could win even under the bleakest of conditions. This passion, dedication, and sacrifice are key leadership qualities beyond being smart, tough, disciplined, and well-conditioned. Brees served as the perfect conduit to communicate Coach Payton’s vision.

And as great as Payton and Brees are, none of this would have happened if ownership and management had not empowered them. By relinquishing some of his authority, Saints general manager Mickey Loomis instilled confidence in Payton and Brees to become the faces of the franchise. Payton clearly defined the kind of players he wanted in his program—smart, tough, disciplined, high character—and Loomis and the personnel department went out and found them. In turn, Payton empowered Brees to lead the team—on and off the field. This sharing and transferring of power resonated throughout the team. Everyone bought in.

After a preseason in 2006 that generated zero wins, the team went to Cleveland for the season opener. The Browns scored a touchdown on a 74-yard pass on the first play from scrimmage. I don’t believe the winning culture had been entrenched in our team by that time, and I could see players thinking, Here we go again. The play was called back because of a holding penalty. We proceeded to win the game thanks to four field goals by John Carney. The next week we went to Green Bay and beat the Packers 34–27, avenging a 52–3 loss from the previous season. In Week 3, the NFL scheduled a Monday night game against our division rival, the Atlanta Falcons. The Falcons were 2–0 and three-point favorites. But this was a homecoming for the team and the city after Hurricane Katrina, and the Falcons never had a chance. Final score: Saints 23–3.

The 3–0 start helped validate the front-office decision to hire Coach Payton as well as Payton’s choice to elevate Drew Brees as the team leader. We went on to finish 10–6, win the NFC South, and make the franchise’s first-ever appearance in the NFC Championship Game. The season had reestablished the team into the city of New Orleans and its culture. The team did not win the Super Bowl that year, and some fine-tuning would be needed before we reached that level, but this allowed the organization to silence some critics and instill the belief that this was an emerging first-class operation. Thanks to Drew and Coach Payton, a winning culture had been established. The days of eating at ramshackle chicken buffets were over for the New Orleans Saints.

Steve Gleason played most of his career with the New Orleans Saints. In 2019, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for his contributions to ALS awareness.

Prologue

The Superdome was melting down.

Deshaun Watson and the Houston Texans had just stunned the New Orleans Saints with a go-ahead touchdown with 37 seconds left in their game on September 29, 2019. On consecutive plays, DeAndre Hopkins and Kenny Stills somehow got behind the Saints secondary for catches of 38 and 37 yards, respectively, the latter resulting in the touchdown.

Only seconds earlier, the Dome was celebrating kicker Wil Lutz’s 47-yard field goal with 50 seconds left. With the Texans out of timeouts and nearly out of time, the Saints looked assured of winning their first season opener in five years. Then everything came unraveled. In the span of 13 head-spinning seconds, the Saints’ 27–21 lead had flipped into a 28–27 deficit.

Saints fans, who had suffered through heart-breaking, last-second playoff losses to the Minnesota Vikings and Los Angeles Rams each of the previous two seasons, were beside themselves. That it was Stills, a former Saints draft pick, who caught the go-ahead score made the situation even more disgusting.

How could this happen?!

Not again!

Incredulous fans stirred and fidgeted as Drew Brees and the Saints offense took the field after the touchback on the ensuing kickoff. The Saints had 37 seconds and one timeout to work with. They needed to gain about 35 yards to reach Lutz’s range for a potential game-winning field goal attempt. The situation was bleak. The Saints’ win probability was 27 percent. But with Brees pulling the trigger, Saints fans had long ago learned that anything was possible.

Entering the 2019 season, Brees had orchestrated 36 fourth-quarter comebacks in his 19-year NFL career, more than any quarterback in NFL history except Peyton Manning and Tom Brady. And during his 14-year tenure with the Saints and head coach Sean Payton, he had

become a master of the two-minute offense. During the final two minutes of games, his Total Quarterback Rating, a statistical metric used to measure a quarterback’s overall passing efficiency, was the best in the NFL from 2017 to 2019, according to ESPN.

To watch Payton and Brees operate in the two-minute drill is to watch true football genius at work. This is where all of their practice, preparation, and planning materialize and coalesce. They know these chaotic, pressure-packed seconds are often what separate great teams from good ones and Hall of Fame quarterbacks and coaches from average ones.

Given the inherent parity of the NFL, an inordinate number of games go down to the wire. During the first 14 weeks of the 2019 NFL season alone, 140 of 208 games (67.3 percent) were within one score during the fourth quarter, and 112 of those (53.8 percent) were decided by eight or fewer points.

For Brees, the intensity and pressure of the two-minute drill is the ultimate test of a quarterback. Over the course of his career, he has grown to embrace the challenge and thrive in the moment.

For Payton, the two-minute offense is the validation or condemnation of a head coach’s offseason preparation and weekly game plan. A former record-setting quarterback at Eastern Illinois, Payton has a unique understanding of the two-minute offense and its impact on winning and losing games. Payton sees the two-minute drill as the ultimate pop quiz for an offense. To prepare his team for the moment, he puts his players through countless two-minute scenarios during offseason practices. Every training camp practice ends with some form of two-minute drill between the offense and defense. The variables—score, timeouts available, time remaining, yards to go—always change to ratchet up the challenge of the situation.

One minute, three seconds to go, trailing by five points, two timeouts, ball on your own 41.

Forty-eight seconds left, no timeouts, ball at your own 29, you need a field goal.

The two-minute planning carries over to the regular season. During the weekly game-planning, Payton and the offensive staff install plays they feel will be successful against the upcoming opponent based on their defensive tendencies in previous games. On the night before each game, Payton and Brees meet to go over the game plan and categorize Brees’ favorite plays. The two-minute drill is always a key part of the meeting. No one leaves the room until they feel comfortable with the two-minute plan going into the game.

Payton and Brees

Payton and Brees